Introduction

Mute Swans (whose Latin species name is cygnus olor) are intelligent, majestic, orange-beaked water birds. They have been the subject of myth and art and a symbol of beauty and love for centuries. They are admired and beloved by many in Canada and around the world for their lasting pair bonds and the care both parents give to raising their young.

Identification

Colouring

Adult Mute Swans all have white feathers and orange beaks – but their feet give clues as to what they looked like as cygnets (young swans). That’s because there are two colour “morphs” or variations of swan. “Royal” morphs are greyish-brown as cygnets and retain dark grey or black feet into adulthood. “Polish” or “leucistic” morphs are beigy-white as cygnets and have lighter beige feet even as adults. In the UK, the monarch, now King Charles, has the right to claim any Mute Swans in open water. The Royal morph, which is the more common in the UK, takes its name from that long association with the crown. Over a century ago “Polish” was attached to the lighter morphs because birds imported to Britain from Poland and eastern Europe often contained this variation. “Leucistic” refers to a partial loss of pigmentation.

Royals are more common in North America but both morphs occur and can occur within the same brood.

As real feathers grow in and replace the cygnets’ original fluffy down, both morphs get whiter, though Royals retain patches of darker feathers for 12 months or more. Royal morphs’ beaks also typically take longer to change from the juvenile black to the bright orange colour they have when mature.

When they are mature the only way to tell a Royal from a Polish is to see the colour of their feet.

Size

Fully grown males weigh approximately 26 lbs/12 kgs and females approximately 22 lbs/10 kgs. Their wingspan is over 5 feet/ 150 cm.

The only waterbird larger than Mute Swans are Trumpeter Swans, distinguished by their black beaks and trumpet-like calls.

photo credit: Elizabeth Fitzpatrick

Life Cycle

After leaving their parents at six to 10 months of age, juvenile swans often live and travel in flocks until they reach sexual maturity at two or three years old. They then select a mate.

Mating and Breeding

As breeding season begins, the male (called the cob) and the female (called the pen) spend about three weeks in March and April building a nest. They pick a place for the nest that will be as safe as possible from predators and flooding, but close enough to the water that their cygnets will be able to get in soon after they hatch.

The swans’ mating ritual begins with calls and greetings, synchronized neck movements, and rhythmic head-dunking. The cob then positions himself on the pen’s back. He uses his beak to pull up on her neck, so her head is not submerged. Mating concludes with the swans rising out of the water, chest to chest, and purring.

During breeding season, the pen lays an egg every day or two until the clutch (complete set of eggs) numbers somewhere between five and nine eggs. She does not start incubating the eggs until the clutch is complete. During incubation the pen stays on the nest continuously and rarely leaves it. She develops a nearly featherless area on her abdomen, called a brood patch, where her almost-bare skill will come in contact with the eggs and keep them warmed. She also regularly rotates the eggs with her beak, so they heat and develop evenly. This is how Mute Swans’ eggs hatch at the same time, despite being laid over many days.

Because the pen does not leave the nest often, even to eat, she grows weaker and increasingly vulnerable. The cob sleeps on land near her at night (not on the water, as both would often do at other times of year), to protect her and the eggs. The balance of the time he can often be found patrolling their territory to keep out other swans. Other swans could be competitors for his family’s territory and would attack and possibly kill his cygnets.

photo credit: Ann Brokelman

Hatching

About 35 days after incubation starts, all eggs hatch within a day of each other, usually in May. The cygnets use an “egg tooth,” a small protrusion on their bills, to score the inside of the egg shells, make cracks, and spread those cracks into holes from which they can emerge. Hatching can take several hours and is very tiring for the babies. When they first hatch they are grey and wet, but soon dry off and become fluffy. At this stage their bills are black.

They spend their first several hours in the nest under their mother’s outspread wings. They sleep and begin to explore their new environment.

A few days after hatching the family abandons the nest. Any unhatched eggs are left behind. They will not return to the nest after this, though the parents will likely use the same site next spring if they found it safe and successful.

photo credit: Kelly Duffin

Pair Bonds and Family Ties

Mute Swans are very loyal. They mate for life and are dedicated co-parents who raise their young together. Both parents will get the cygnets (baby swans) into the water to swim within 48 hours of hatching. Both parents will pull up underwater plants for the cygnets to eat early on, then teach them to forage for themselves. When the cygnets are big enough, both parents show them how to dabble (upend) to reach food on their own. Both parents model the critical skill of preening (see Common Behaviours), which is bathing, cleaning their feathers, and spreading oil over them from a gland in their tail. When the cygnets’ feathers grow in, both parents teach them to fly (see Flying).

Parent swans teach their young to recognize and avoid dangers. If the adults perceive a threat they will make a danger call to alert the family and quickly get the cygnets to safety. They will model defense postures – opening their wings and hissing at the danger.

As the cygnets grow up, the parents will also teach them other defense strategies. The cob (male/father) is the primary defender of the territory. To keep out other swans, who would be competition, he will patrol and chase out any intruders by busking (puffing up) and advancing quickly until the intruders fly away. The pen (female/mother) will also defend if necessary. Cygnets need to learn this skill and at four or five months old they start to test it out. But they are still young and often realize they don’t have the life experience to win a real battle. Very often they beat a hasty retreat behind their dad for protection.

Mute Swan parents share these duties, but if one parent dies the other will take over and raise the cygnets alone.

A swan who has lost a mate is likely to seek out another.

Diet

Mute Swans’ diet consists primarily of underwater plants (called submerged or subaquatic vegetation or SAV), which they reach by upending and extending their necks underwater. Parents will pull up SAV for their cygnets to eat, or paddle to churn up water plants and bugs before the cygnets are able to fully fend for themselves.

Because of their long necks they must drink as they eat. Feeding them on the shore, especially human food, is dangerous. They can choke without water.

Processed foods like bread can also cause a condition called “angel wing” in cygnets, where the bones in their wings develop abnormally. This can make them flightless and very vulnerable to predators.

Moulting

Every year during the late summer swans begin looking a little scruffy because they have started to moult (also spelled molt). Moulting is when they lose most or all of their “old” feathers and grow fresh new ones. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology explains: “A feather is a ‘dead’ structure, analogous to hair or nails in humans and made of the same basic ingredient, the protein keratin. This means that when they get damaged, feathers can’t heal themselves – they have to be completely replaced.” This replacement is called moult.

Mute Swans’ entire moulting process takes about six weeks. Their flight feathers are among those they lose so they are grounded while moulting.

Because they can’t fly and because it takes a lot of energy to grow a new set of feathers, the timing of their moult is important. The nesting season, with its energy demands, is over by late summer. They might need to fly a good distance in winter, if their territory freezes and they have to get to open water, but winter is still a few months away.

If a bonded pair of Mute Swans has cygnets, the parents will moult consecutively rather than at the same time, so one can always fly. Typically, the pen (female) begins first.

During their moult they appear to have shortened and more wispy wings and often sport loose and dangling feathers, then the “shoots” start to emerge. At the end of the process they’ll have a clean and healthy set of new feathers to get them through another year.

Flying

Fall is the season that cygnets (young swans) learn to fly. With their feathers fully grown, they prepare by stretching their wings and flapping to build up the muscles they need to get airborne.

The parents’ moults (which is when they lose and regrow their feathers – see Moulting), will be complete so they are able to fly again and give the lessons. Typically, they gather the cygnets in one area of water, with one parent in front and one in back, facing the wind. Because of their size, they need a good stretch of water to take off and the start of their flights look like splashy running until they get lift off and tuck their legs behind them. In the early attempts, most cygnets do their best to follow their parents but very often a few can’t quite do it and are left flapping vigorously in place. With time and practice they get the hang of it. They get higher in the air. They start to calibrate their landings better, which they often overshoot initially. Their flights also become longer as they build their endurance.

Swans are large birds so to get lift off they need strong chest muscles and light bones. Indeed, many of their bones are hollow and they have relatively fewer bones than other animals of their size, so that they are light enough to fly. Like many other birds, they also have a more efficient breathing system than humans and many mammals. This enables them to breathe up to 10 times faster when they fly to get enough oxygen for the exertion.

On long flights swans can get thousands of feet in the air but typically they fly quite low for short distances and usually don’t get higher than 400 to 500 feet.

Flight is obviously a critical skill for birds and one of their defenses, but especially for youngsters without much experience, it has dangers. Swans’ eyes are on the sides of their heads, which is helpful in spotting predators, but it also means they don’t see especially well in front of them and so can hit obstacles like wires and poles. They can also misjudge geographic features. With snow in winter a dark road can look like open water, for instance. Cygnet mortality is highest in the first two weeks of their lives because they are most vulnerable, but fledging, (flying away from their parents) is the second riskiest time.

Still, fly away they must. If the cygnets don’t get the urge to strike out on their own their parents will insist on it, especially the father (the cob) who will chase them out in winter if they haven’t left yet. By then the parents are thinking about their next brood and they will have taught the current brood all they can about life as a grown-up swan. It’s time for the cygnets to spread their wings.

Mortality

Mute Swan eggs are very vulnerable to almost any predator – from herons to raccoons, foxes, minks, and coyotes.

If the eggs hatch, Mute Swans have about a 50% survival rate to age one. Most mortality occurs in the first two weeks of life. Young cygnets’ most common causes of death include cold and storms and predation.

For older juveniles and adults, causes of death include boats, cars, fishing line and hooks, fireworks, hydro lines, poles, netting, and other human structures and activity. Coyotes, wolves, foxes, offleash dogs, minks, snapping turtles, rats, gulls, and raccoons are all predators of swans, and injure or kill swans much more frequently than the reverse. Disease and bad weather can also kill adults. Many Mute Swans died in Ontario due to starvation in the extremely cold winters of 2014 and 2015 and due to flooding in 2017.

Population

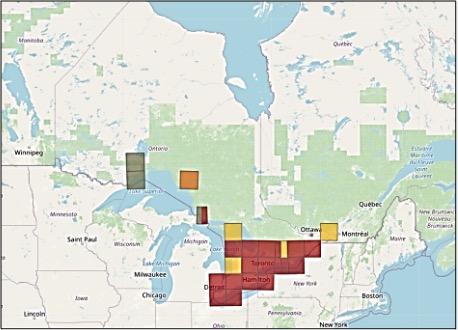

The Midsummer Mute Swan Survey used to be flown in the Lower Great Lakes every three years. The last one flown before COVID was in 2017 and counted a total abundance of 4,251 Mute Swans in both aerial and ground surveys. In the Lower Great Lakes only, 4,103 Mute Swans were counted.

The carrying capacity (which is the maximum population that can be sustained in a given environment) for Mute Swans in the Lower Great Lakes is estimated at 30,000 birds meaning that by 2017 they had reached 14% of their carrying capacity. It is typical for a species’ population to increase before leveling off as it approaches carrying capacity

The Great Lakes Marsh Monitoring Program (MMP) reported in their 2023 newsletter that the average annual growth rate of the Mute Swan population was 2.7% between 1995 and 2022. It also found that their numbers were decreasing inland. In the same time period, Trumpeter Swan abundance grew at an average annual rate of 6%.

Over a similar time horizon, the Midwinter Waterfowl Count shows a largely stable Mute Swan population in the Niagara, Hamilton, and Toronto regions between 2002 and 2023.

The Christmas Bird Count found a similar trend over the decade between 2002 and 2022, with Mute Swan abundance increasing at an average annual rate of 3% (Trumpeters 9%).

However, the 2017 Midsummer Mute Swan Survey showed that Mute Swan numbers – including numbers of adults – actually declined significantly between 2014 and 2017 in one stretch of the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area:

Humber Bay to Hamilton Harbour

| Year | Adults | Cygnets | Total Birds |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 127 | 7 | 134 |

| 2017 | 96 | 0 | 96 |

| Change | -38 | ||

| Annual Growth | –28% | ||

In terms of relative abundance, Mute Swans are a fraction of other waterbird species. The 2022 Christmas Bird Count found 2,800 Mute Swans in Ontario while the same survey counted 196,742 Canada Geese (Branta canadensis) and 74,424 Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos).

Range and Distribution

Mute Swans’ range is not expanding in Ontario. The Third Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas (2021-2025) illustrates that they are concentrated in the Lower Great Lakes. This is largely unchanged from their range and distribution in the Second Atlas (2001-2005). They do well in degraded and urban habitat. Other species, including Canada Geese, and Mallards, have comparatively larger ranges and are more distributed across the province. Trumpeter Swans are also more broadly distributed, including inland.

Common Behaviours

Preening and Bathing

Mute Swans have approximately 25,000 feathers. Preening involves both cleaning them to ensure they are free from dirt and parasites, and distributing oil over them, from a gland near their tail (called the uropygial gland). This is to ensure the feathers remain waterproof. Being waterproof is critical to swans’ survival, especially in winter.

Bathing is another way swans keep clean. A swan bath involves vigorous flapping, dunking, and surfacing, often while rolling from one side to the other. It is quite dramatic, can go on for several minutes, and once one swan starts, others in the family or flock tend to join in for a group bath time.

Sounds

Mute Swans are not actually mute. Cygnets (the young) making cheeping noises in their early months, then begin to grunt. Adults use specific calls to summon their young or warn of danger. They also grunt, snort, and even, on occasion, purr.

Cheeping and grunting, combined with head bobs, is a form of greeting.

Flocking

When winter approaches more Mute Swans start to move south. Unlike some migratory birds, swans do not go as far as the southern US, but they do need to find a body of water, like the Great Lakes in Canada, that is unlikely to freeze over in winter. They must have water to drink and access to underwater plants, which are their primary source of food. This year’s cygnets (juvenile swans) will also soon leave or be evicted from their parents’ territory and will need to find a flock to join.

This means flocks tend to be juveniles who haven’t yet found a mate, older singles, and unsuccessful breeding pairs.

Bonded pairs of swans with a nest site will try to stay put to defend their territory for next year’s breeding season but will also need to move south if their body of water freezes.

Flocks will start to disperse in spring. New pair bonds will have formed so young pairs will go off in search of nesting territory. Older pairs will return to their previous nest sites once the water thaws.

Stretching Their Legs

Swans often stick their feet out. They may rest them on their backs or stretch their legs out behind their bodies. They do this both on water and on land, when they are standing or loafing. It is not known why this is a common swan behaviour but theories include that it might be a temperature regulating mechanism or that it might just feel good to stretch. Whatever the reason, it is normal and does not indicate a broken leg or an injury.

Defending Territory

Paired Mute Swans defend large territories and keep out other Mutes. The female (pen) will defend in certain circumstances, such as if the male (cob) is away, or there is a threat to her babies, or her mate is moulting and cannot fly. Otherwise, this is primarily the cob’s job.

Where there is a border between two pairs’ territories, the cobs will use a Rotation Display, where they circle in the water close to each other, marking the border and warning the other not to cross.

If a single or pair of other Mute Swans enters a resident nesting pair’s territory, the cob will give chase. Often the intruders take the hint and retreat. If they don’t, the cob, and if necessary the pen, will assume their busking postures – wings up and neck bent far back – and race at the challengers. If the new pair wants and believes they can win a resident pair’s territory, real fights can occur. They will involve flying and can even see one cob mount another, pushing his head underwater. Very occasionally this results in the death of a swan but more often one pair will cede the territory to the other.

While Mute Swans peck at other waterbirds from time to time, they generally tolerate them and their young. Their fight for territory is primarily with other swans.

Our Bond with Mute Swans

Mute swans are large, visible, tend to live in urban wetlands, and are accustomed to people. This means we humans can watch and get to know them in ways that are quite unique.

Humans should not be interacting with larger mammals, such as foxes and coyotes. Smaller mammals, like squirrels, are often indistinguishable from each other. And other waterbirds, like ducks and geese, have babies that soon look just like their parents.

Mute Swans, by contrast, tend to be fewer in number than other waterbirds and because the parents protect the territory, they become longstanding or returning residents that we recognize and get to know. They recognize individual people so they can also get to know us.

Being urban animals, they often build nests within view, and we can watch the nest taking shape. Within a day of hatching, we can witness the cygnets’ first swim. Cygnets’ grey/brown feathers take months to change to white, so the babies remain identifiable as we watch them grow up, learn to forage, make their first awkward flights, and ultimately, fly off to start their own lives.

These factors mean we can have a genuine connection to a wild animal – close to home if we are fortunate enough to live near a lake or pond.

As Dan Keel says in his book Swan, “I had a bond with swans that I could not forge with any other bird.” That bond is one of life’s great joys.